About cyanobacteria (harmful algal blooms)

Cyanotoxins, which can cause health problems, are produced by naturally occurring cyanobacteria, often called "harmful algal blooms” or HABs. HABs occur in freshwater lakes and streams as well as saltwater and brackish environments. HABs are becoming more common and severe due to changes in the climate.

- Warmer water, longer growing seasons, and more frequent droughts create ideal conditions for cyanobacteria to thrive.

- Heavier storms wash more nutrients into lakes and rivers, fueling growth.

These changes can lead to more toxic and longer-lasting blooms, threatening water quality, public health, and aquatic ecosystems.

Impacts of HABs

Health risks: HABs are naturally occurring, but they can pose serious health risks to people and animals.

- Exposure can happen through ingestion, skin contact, or inhalation of toxins or cyanobacterial cells.

- Symptoms range from mild (e.g., mild rash, headache, ) to severe (e.g., respiratory and gastrointestinal distress) and may require medical attention.

- Animals and pets, including dogs, are at high risk—ingesting contaminated water or licking cyanobacteria (HABs material) off their fur or paws can lead to serious illness or even death.

More information on the health effects of HABs exposure and how to report symptoms related to HABs exposure can be found here.

Drinking water: About 60% of Lake County residents get drinking water from Clear Lake.

- Public water systems in Lake County monitor and treat drinking water to remove cyanotoxins.

- However, many homes use self-supplied water (from Clear Lake, streams, or wells), and typical home filtration systems may not remove toxins effectively.

- Residents using self-supplied water systems should be especially cautious during bloom events.

Impacts on community and environment: HABs can impact daily life and the local economy.

- Recreation- HABs often make beaches, inlets, and swimming areas unsafe or unpleasant.

- Tribal cultural practices- Clear Lake and surrounding waters hold deep meaning for local Tribes, who rely on these sites for cultural practices.

- Quality of life- HABs can cause strong odors, keeping people from enjoying areas near water, including parks and backyards.

- Economic impacts- Large, prolonged HABs can hurt tourism and local businesses

Populations at risk

- Those living near the shore of Clear Lake, particularly in areas such as the Lower Lake arms, which is highly impacted, are most likely to be exposed to HABs near their homes through aerosolized bloom material that may be inhaled, swimming in areas with blooms, or using household water from a self-supplied system.

- Visitors to the area who may not be familiar with the hazards may also be at risk if they choose to wade or swim in contaminated areas.

- Tribal cultural activities may expose participants to cyanotoxins or bloom material.

- Outdoor workers, including farmworkers or those working in recreation may be exposed during blooms if nearby the lake or its tributaries and watersheds.

- Unhoused people who may stay near the lake or use it as bathing or cooling option are at increased risk during blooms.

- Anyone who uses the lake to cool down during extreme heat events, particularly by swimming, is at risk if there is or has been a recent bloom.

HABs in Lake County

Clear Lake has experienced a significant and worsening trend of HABs. Though HABs have occurred naturally and have been documented since the early 20th century, the past several decades have seen a rise in both the frequency and severity of these events due to increased nutrient inputs, warmer temperatures, and other environmental changes that have intensified bloom conditions.

Monitoring data from 2011 to 2019 show that cyanotoxins in Clear Lake, produced by the HABs or cyanobacteria, frequently exceeded California's health advisory levels, with some concentrations surpassing the "Danger" threshold of 20 µg/L. HABs typically occur in late spring and summer, turning the lake bright green. In May 2024, a bloom was so large that it was visible from space.

California tracks significant HABs via reports and satellite monitoring. More information can be found here.

Highlights from the CHARM survey and interviews

Survey responses

- Over the next 20 years, 54% of survey and interview respondents believe there will be more cyanobacterial blooms/HABs in Lake County.

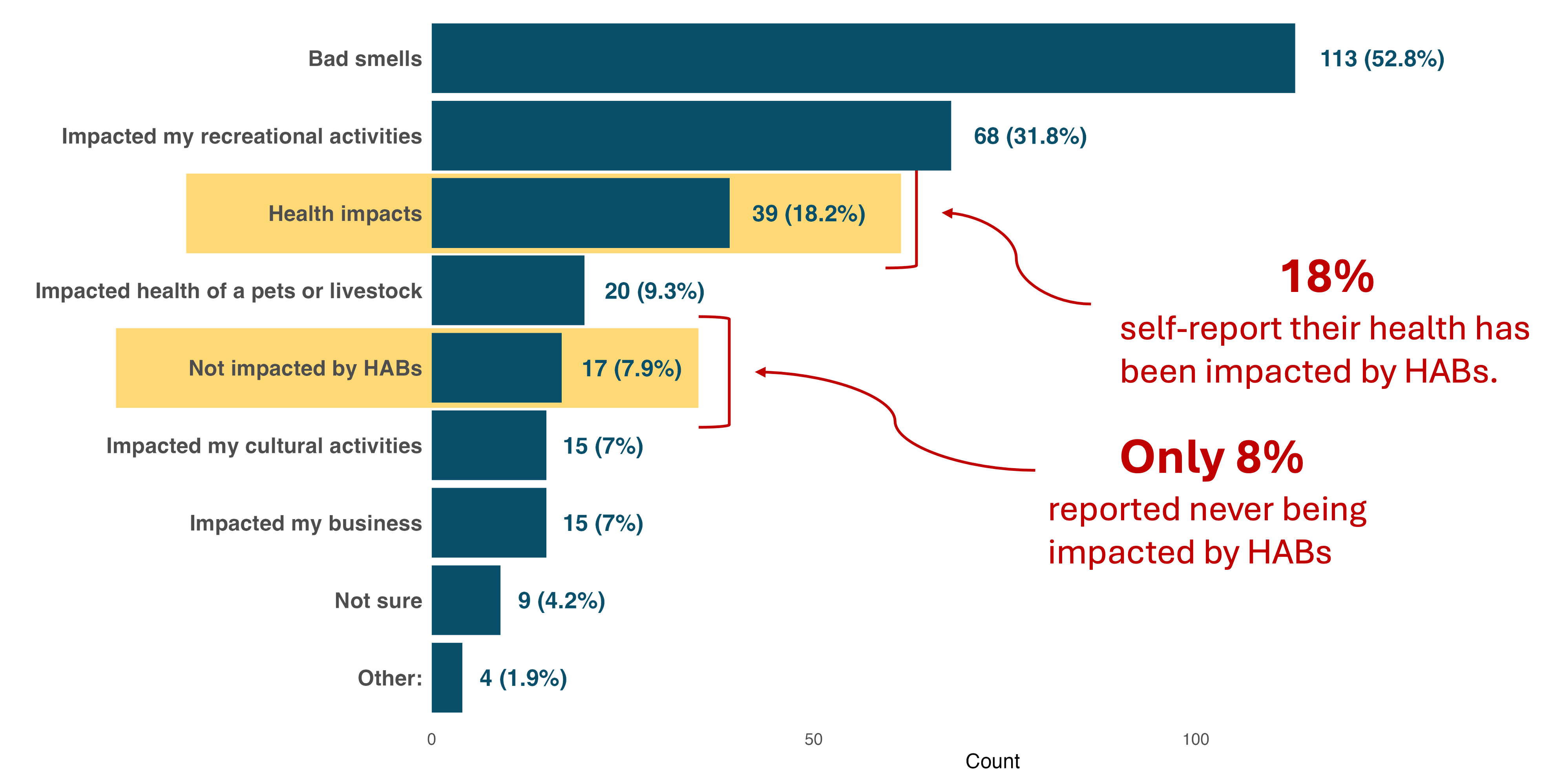

- Respondents noted the following experiences of cyanobacterial blooms/HABs:

When asked about how they’d like to be notified about HABs

- 40% mentioned signage at HABs sites

- 33% wanted notifications via online news sources

- 28% wanted to see an alert from LakeCoAlert, other warning systems, or Facebook

Only half of respondents (48%) already knew that HABs could affect human and animal health, and 41% knew what they are or how they specifically impact humans and animals.

Fewer respondents were aware of symptoms (22%), where to get information (23%), or current toxin levels (10%), and 7% reported no prior knowledge of cyanobacterial blooms or HABs.

Community voices

"Yeah, I live near the lake. And it's, it's crazy how the water turns from green to blue and stuff like that. And the smell, I know sometimes that they try to get the water circulating to help it to not be as bad. Yeah, it's just crazy. I don't do why it's so bad like, over the years before, I remember going up, it was never this bad. Now it's just just super bad. Yeah, and they even say it's bad for pets too."

"All I know is that, as it's happening, it's getting more frequent and more often each year that I'm alive. You know, when I was a youngster and everything, we always were able to go enjoy the lake. Didn't matter what time of year it was. Now, obviously, we've even had our most the biggest event we have at Big Valley, the Tule boats festivals have been canceled because of cyanobacteria outbreaks."

"[It smells] like raw sewage - I took my I took my nephew down to go fishing in the Keys and you throw your lure out and it goes splat on top...it was not worth it. It was just disgusting."

Tribal resident:

"I just want to speak about the cyanobacteria outbreaks and the health of the lake. You know, it's so important for our people in the next seven generations to have the hitch here and available, whether they're just being studied or eventually gathered again, even once a year, for our people to eat and to have that connection. Because we lost it. You know, we lost it. As a young man, I used to go to Upper Lake with my uncles and my father, and we would collect hitch. It was something I've never experienced anywhere else. A lot of people see them salmon the way they run, but they run black here in these creeks, and you could just go catch them with your hand, scoop them out. We'd scoop them out. We'd bring them home. We'd dry them. We'd hang them on the clothesline. We'd salt and brine them. We'd have them for the whole year just to eat them like potato chips, and we got to protect them as much as possible and work together as Tribes."

Improving resilience to HABs

Increasing awareness

Systems of communication that alert self-supplied water users, swimmers, kayakers, and others coming into contact with HABs are critical to keeping Lake County residents and visitors safe. Communicating at the site for recreational exposures (such as signage) and reminders via multiple routes (e.g., email, text, mailed) to those who may be exposed through their self-supplied water system are examples of ways to build resilience in this area.

These systems require coordination and should be integrated with and leverage existing efforts to monitor and communicate about HABs. For example, the Big Valley Band of Pomo Indians monitors HABs in Clear Lake and streams that feed the lake, and posts updates regularly on hazards. California’s Water Quality Monitoring Council offers pictures of blooms and tips on staying safe during recreational activities, as does the CDC. California also offers information on keeping pets and livestock safe from exposure.

Improving infrastructure

Residents relying on self-supplied household water systems should receive information and support to ensure that they have home filtration options that are maintained and effective. Projects like Cal-WATCH (California Water: Assessment of Toxins for Community Health) are providing free drinking water testing and identifying key infrastructure needs; however there is currently no longer funding to continue this project.

Improved lake and watershed management

Some strategies for reducing HABs include reducing nutrient runoff through better farming practices and septic upgrades and restoring wetlands and riparian areas to naturally filter pollutants. Water body managers in Lake County and other heavily impacted regions are exploring bloom mitigation, or taking steps to reduce the frequency, intensity, and duration of HABs. HAB mitigation is complex and may require significant resources and coordination across county, state, and Tribal partners to be accomplished safely and effectively. California’s Water Quality Monitoring Council has basic information on mitigation processes and resources.

<< Extreme heat